Your basket is currently empty!

Theologians of Dance

Every once in a while, a blogger should pick up an actual book on his or her topic. A book (in case you’ve forgotten) is a pile of paper pages with printing on them, sewn together and then sewed or glued into a foldable cardboard frame. The company that does the printing, sewing and glueing, called a publisher, gets experts to read through the blogpost manuscript (nowadays a computer file saved by the writer) to tell the former if the latter is worth its printing, sewing, glueing and promotional activities.

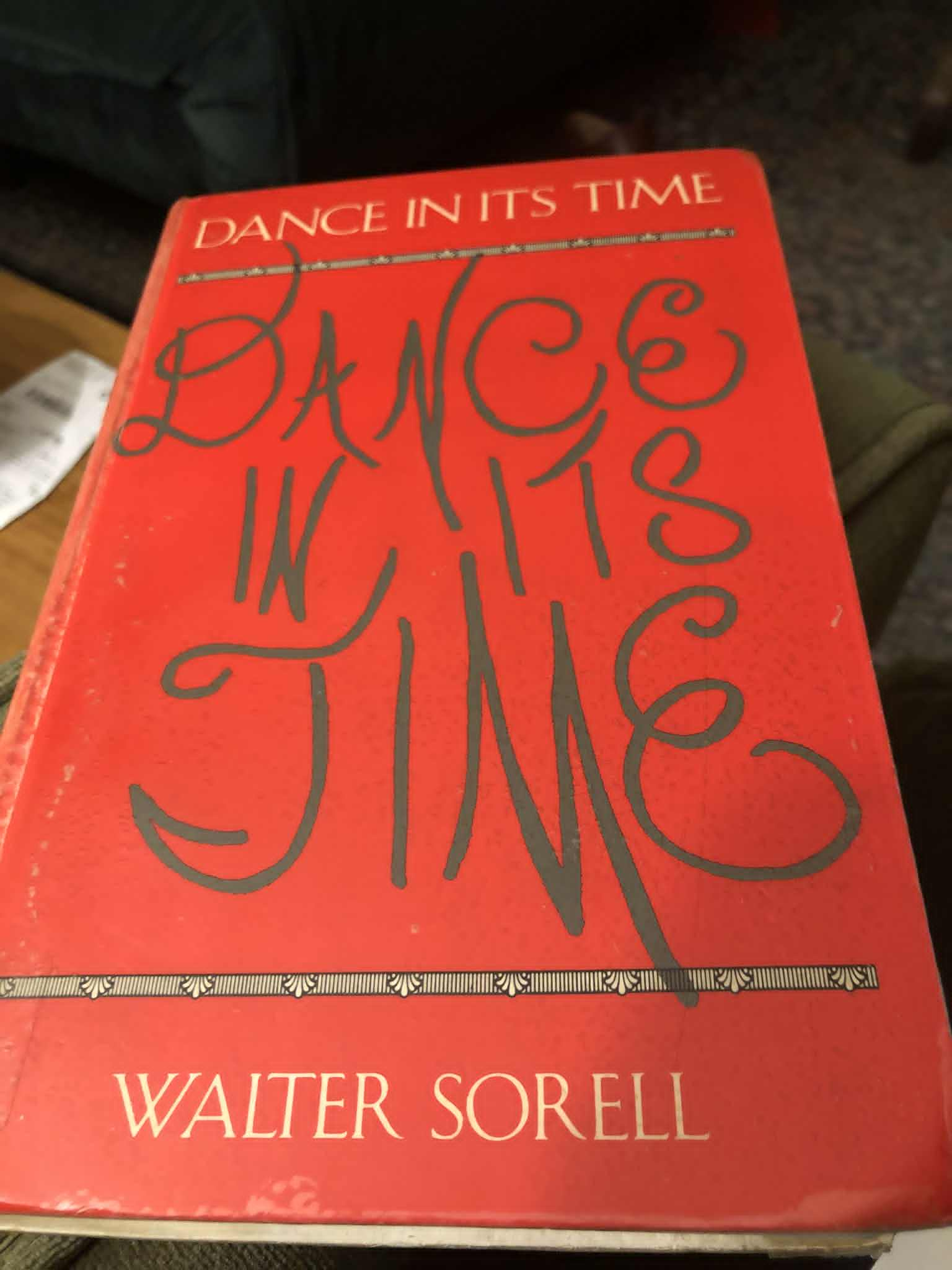

And so it must have been with Walter Sorell’s Dance In Its Time, for Columbia University Press in New York published it in 1981. Sorell himself was a professor emeritus of Columbia University, so Columbia probably trusted him, but all the same they probably sent his Substack manuscript around to his equally learned friends and rivals to check that he wasn’t just making stuff up. That is one of many ways books are superior to theo-bros screaming nonsense on YouTube for clicks.

Sorell is so interested in locating dance in its time that his work is more of a tour of western history than a discussion of dance. (D.H. Lawrence, Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Gerhart Hauptmann, Henrik Ibsen, Bernard Shaw, Maurice Maeterlinck, Claude Debussy, Stéphan Mallarmé, Auguste Rodin and Rainer Maria Rilke are all referenced on page 299.) However, Sorell is nothing if not thorough, and so he name-checks four 16th-17th century Catholic theologians on the topic.

No doubt there were any number of kinds of clerics during the Counter-Reformation, but when it comes to dancing, I suspect there were only three: ordinary priests trying to frighten illiterates into good behaviour, dance teachers, and scholars. Sorell lists four scholars: Thoinot Arbeau (the pen name of Fr. Jehan Tabourot , canon of Langres, 1520-1595); Fr. Martin Mersenne (1588 -1648); the Abbé Michel de Pure (1620 -1680), chaplain to Louis XIV; and the Abbé Jean-Baptiste Du Bos (1670 – 1742).

Thoinot Arbeau, Sorell tells us, “recorded the dances known in the sixteen century. adding historical comparisons with antiquity and an evaluation of the dances from the aesthetic and moral viewpoints.” In his 1589 Orchésographie, Arbeau refers to dancing as an “honourable exercise.” He also introduces a sympathetic character named Capriol who mourns, “I lack the skill in dancing to please the young ladies, on whom, it seems to me, depends the entire reputation of a young man of marriageable age.”

Father Marin Mersenne wrote a book called Harmonie Universelle, “full of searching thoughts about music, dance and life.” In this 1636 encyclopaedia of music, Fr. Mersenne mentions many dances, including “La Volte” which has something in common with the more exciting form of swing dancing:

The Volte seems, from its name, which means to turn, to come from Italy, because it is danced by turning: although it has been in France for so long that it can be said to be native. It may also have this name because, after a few straight steps, the man makes the woman jump, leading her in a turning motion, and after leading her around for a while, he takes her by the left arm … and turns her several times, lifting her high, as if he wanted to make her fly.

I think I will enjoy reading Harmonie Universelle –but first I must read Orchésographie, for I have quite lost my heart to poor Capriol, who wants to learn how to dance just to be popular with girls and convince one to marry him.

The Abbé Michel de Pure wrote about dancing in his 1676 (?) Idée des Spectacles ancient et nouveux, both as a social activity as the new art form of ballet. He apparently drew a fat line between social dance and ballet, disapproving of “the noblemen who, he felt, participated in ballets for the sake of ‘vanity and personal interest’.”

“He expected the dancing master to make a clear distinction between the social dance and ballets as a new art form,” Sorell continues.

Then the Abbé Jean-Baptise du Bos wrote about dance in his 1719 Réflexions Critiques Sur la Poésie et la Peinture. Perhaps in contrast to Fr. Mersenne, who thought the “principal end” of all art “was to delight the cultivated listener, and not rouse his passions”, Fr. Du Bos thought (I am informed by French Wiki) that “art cannot be merely beautiful, but must also stir the heart.”

“These theologians were fascinated by movement, dance, and mime, by all that reveals human beings and by what we can reveal without words,” writes Sorell. “Like Arbeau, they were humanists and came, through the study of antiquity, to think of movement and dance in their own time. They may, in an age and in a world torn by religious strife, have looked for a unifying gesture that one God gave to all of us: movement and the ability to make people move to their hearts’ delight and by the will of their minds.”

“But what about these clerical dance teachers?” I hear my readers cry. Well, that is a subject for another day. The point of this post is to begin a conversation with proper theologians who thought seriously about dance.

Thank you to all those who made the Michaelmas Dance 2025 such a success! A very Happy Feast Day to you all. Coorie in!