Your basket is currently empty!

“The Fair Assembly”: Social Dancing in Edinburgh from 1705

The best general history of social dancing in Scotland I have found so far is called Oh, How We Danced: The History of Ballroom Dancing in Scotland by Elizabeth Casciani (1994), and you will be able to find it in the Music department of the Edinburgh Central Library (GV1619) after I return it. Most, but not all, of the information I will impart in this short address can be found there.

This will be a rapid review of social dancing in Edinburgh in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, and one of the themes is opposition to public, or semi-public, dance parties. Dance assemblies first emerged in post-Reformation Edinburgh against a backdrop of “religious and political unrest” (Casciani, 1) among the Protestant, predominantly Calvinist, majority. In fact, the the religious scruples of Edinburghers against dancing, regarded as frivolous at best, could be stronger than deference to the rich and aristocratic (which, one might admit, seems never to have been as strong in Scotland as in England).

The Eighteenth Century

The first recorded instances of dance parties in Edinburgh began in 1705 when John, 3rd Earl of Selkirk, formed a fashionable and exclusive club called “The Horn Order” which adopted the horn spoon as their badge. (See James Grant, Old and New Edinburgh, Vol 5., page 122.)As Casciani writes, “A small gathering of ladies and gentlemen braved the wrath of the Scottish Church and enjoyed dancing the Minuet. Masquerades were also held, and there were accusations of promiscuity and scandal” (Casciani, 3).

But the first regularly organised dances began in 1710 with the advent of the West Bow Assembly. This was organised by a group of aristocratic ladies, called directresses, and held in rented rooms in a building (since demolished) on the old West Bow. The area around Victoria Street (the current West Bow) and the Grassmarket has undergone considerable change since then, but I currently believe the exact location is on Johnston Terrace, where St. Columba’s Free Church is now. The rooms were described thusly: “A narrow spiral stair led to a lofty wainscotted room, with a fine carved oak ceiling, on the second floor… [There was]a closet or recess forming an out-shot over the street, wherein musicians could retire for refreshments or to rosin their bows” (Robert Chambers, Traditions of Edinburgh, 1824.)

There was much opposition to these dances, including anti-dance sermons, pamphlets and even a physical attack. As Casciani writes, “On one such occasion, an infuriated mob of zealots assaulted the company and attacked the door of the assembly room, perforating it with red-hot spits” (p. 3).

The weekly West Bow Assemblies were very popular, and the “the whole Bow was packed with sedan chairs and carriages,” writes Casciani (p.3). In 1723 the Assembly moved to a location on what is now called Old Assembly Close on the south side of the High Street. There was renewed opposition, but also support from, for example, the poet Allan Ramsay, who wrote a poem, published in 1723, called “The Fair Assembly”.

In his foreword addressed “to the Managers”, the “Right Honourable Ladies,” Ramsay praised the virtues of public dances and addresses the criticism:

How much is our whole nation indebted to your Ladyships for your reasonable and laudable undertaking to introduce politeness among us by a cheerful entertainment, which is highly for the advantage of both body and mind, in all that is becoming in the brave and the beautiful; well foreseeing that a barbarous rusticity ill suits them, who, in fuller years, must act with an address superior to the common class of mankind; and it is undeniable that nothing pleases more, nor commands more respect, than an easy, disengaged, and genteel manner. What can be more disagreeable than to see one, with a stupid impudence, saying and acting things the most shocking amongst the polite; or others (in plain Scots) blate [be sheepish], and not knowing how to behave […]. It is amazing to imagine, that any are so destitute of good sense and manners as to drop the least unfavourable sentiment against the Fair Assembly.

Ramsay goes on to point out that church meetings, wine, beauty in women, learning and dancing have all been abused for evil–“But will any argue from these that we must have no churches, no wine, no beauties, no literature, no dancing? –Forbid it Heaven!” (Allan Ramsay, “The Fair Assembly” in The Poems of Allan Ramsay, 1800.)

Between 1723 and 1733 there were 255 meetings in the Assembly Rooms in Old Assembly Close. They happened every Thursday from 4 PM until 11 PM in winter and from 6 PM until 11 PM in what was deemed summer. Tickets cost half-a-crown and refreshments (tea, coffee, hot chocolate and biscuits) were extra. Money raised went to such charities as the Poorhouse and the Royal Infirmary–the latter still, of course, existing today.

In 1736 the Edinburgh Assembly moved to what is now 142 High Street, and in 1746 Gavin Hamilton, the man who sold the tickets, took over the rent of the rooms personally. The Assembly began to take Minutes, which ended in 1776. In the intervening 30 years, the dances had raised £7,500. (Approximately £654,415 in today’s currency.) It then moved to Buccleuch street and in 1785 to the George Square Assembly Rooms at 15 Buccleuch Place. According to Casciani , Sir Walter Scott attended the George Square Assemblies in his youth (p.14). At this time, other ballrooms began to open, notably in the hotels springing up in the New Town. And in 1783, the first stone was laid for the Assembly Rooms in George Street, which of course are still there today. The Caledonian Hunt Club held the first ball there in 1787.

According to Casciani, dancing was accepted as a pastime throughout Scotland, even in small towns, by the 1770s (p.12). However, the gentry of the Assemblies did their best to keep ordinary folk out for as long as they could. Originally this was done through cost of the ticket (a skilled workman’s day wage), and the directresses could and would forbid entry to those they didn’t like.

A swift word about Catholics: at least two Catholic Italian ladies, Felice Marcucci and Teresa Rossignoli, were among the many dance instructors, almost always men, who opened dance schools in the 18th century. (Please see Olive Baldwin and Thelma Wilson’s “Mistresses of Dancing-schools in Edinburgh, 1755 – 1814” here.)

Felice Marcucci‘s school was in James’s Court, off the Lawnmarket, in the same building as resided the biographer and diarist James Boswell. Boswell was a rakish sort of chap and complained in his diary that Madame Marcucci was “too strict a religionist” for his flirtations. And Mrs Marcucci found a threat greater than Boswell: in 1779 the writer came home to find the dance teacher taking refuge with his wife as an anti-Catholic mob raged about. Boswell went out to see them burning down a “mass house”, and Mrs Marcucci stayed for dinner.

Teresa Rossignoli was teaching the eldest three daughters of the Duchess of Buccleugh by 1785 and opened a school that year. This closed in 1814, and she taught from 1814 at the Merchant Maidens Hospital School until 1831. This had been founded by banker Mary Erskine and the Company of Merchants of the City of Edinburgh in 1694. It was later refounded as the Mary Erskine school. In 1977, this joined Stewart’s Melville College to form ESMS, now the landlord of the Dean Halls, where Mrs McLean’s Waltzing Party dances today.

The Nineteenth Century

For our purposes, there were three interesting trends in the 19th century: the rise of the monied middle classes, the belief that dancing was an essential part of Scottish social life, and the adoption of new, exciting dances.

As I mentioned, the gentry tried to keep the middle classes out of their assemblies. According to Cascioli, they kept up exclusionary measures as late as the 1880s (p.18). However, by 1800 there were many other places to dance anyway. Everyone who could afford tuition learned to dance and made sure their children did, too. They either learned to dance with a private tutor, at school, or at one of the many dancing schools in town. There must have still been some anti-dancing fervour among the censorious, for Cascioli tells us that teachers advertised in newspapers under the heading “Tuition” rather than dancing (p.33). However, dancing instructors also taught good manners and deportment as well as steps. These were considered crucial to the upwardly mobile, i.e. those who wanted to move easily among the ruling classes.

The primary dances of 18th century Edinburgh were minuets, country dances (originating in England and altered to suit Scottish tunes), cotillions, allemandes, reels and strathspeys. In the 19th century, exciting new dances arrived: the Quadrille in 1816, the Polonaise in 1830, the Polka in the 1840s, and–of course–the controversial Waltz, which first appeared in Almack’s Assembly Rooms in London in 1812 and presumably came to Edinburgh not long after. By the 1837 coronation of Queen Victoria, who loved the Waltz, the dance was “firmly established,” says Cascioli (p.21). She tells us later in her book that the death of Prince Albert in 1861 made dancing much less popular in England, but Scotland kept on dancing.

The Twentieth Century

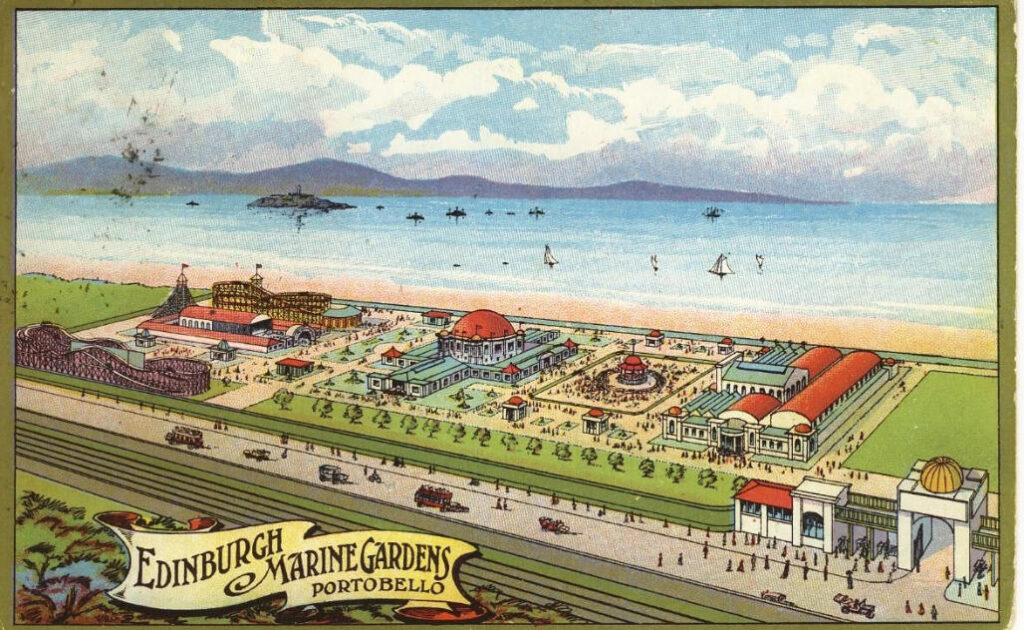

Edinburgh, like other cities in Scotland and around the world, went absolutely dance-mad in the 20th century. Knowing how to dance became a necessary social skill for all social classes. Dancing schools and teachers flourished, and ballrooms proliferated. My favourite example is the Empress Ballroom at the Marine Gardens in Portobello, which was a seaside resort covering 27 acres. The resort opened in 1909, and its ballroom, apparently big enough to seat 3,000 people, opened in 1910.

According to Casioli (p.40), the dance season was now all year around, and by World War I, Edinburghers could dance every afternoon and evening–although I do not believe public ballrooms were open here on Sundays. In 1910, the Waltz was still the most popular dance, although the “Boston” style now dominated. The infamous and ungainly “animal dances”– Grizzly Bear, Turkey Trot and Bunny Hug–appeared, and the tango arrived in Glasgow in 1913 and presumably in Edinburgh soon after. An Edinburgh dance teacher brought the foxtrot back from the USA in 1914. Cascioli writes that the foxtrot was very popular because it was easy to pick up (p.44), and dance teachers began to get nervous. Jazz, with its wild “shimmy” dance, was seen as a huge threat to the trade.

In 1920, 300 dance teachers met in London to discuss strategy, Cascioli tells us (p.45). If I remember correctly, teachers had already decided to hold competitions to discover–and standardise–the most elegant style of ballroom dance, and they did so for the foxtrot, too. By 1924, the Ballroom Branch of the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing had founded the “English style” of waltz, foxtrot, tango and quickstep. That year the Charleston arrived: it was both insanely popular and sternly condemned. Lindy Hop and Jitterbug arrived in the late 1930s, and became extremely popular, thanks to the arrival in the UK of American servicemen in 1941.

Curiously, the upper and middle classes stopped going to dance classes by World War II and so, Cascioli writes, they just “shuffled through” dances at their exclusive clubs and expensive hotels. The vast majority of young Scots, however, learned to dance as well as they could and competed for partners’ attention on the dance floor. They even took part in competitions for big prizes and job opportunities.

“Dance teachers,” professional partners, in the dance palaces, both male and female, earned the same wages as skilled tradesmen and could accept big tips and even expensive presents. (They were absolutely forbidden from “walking home” with customers.) In 1925, Portobello’s Marine Gardens, which hosted 1,000 to 2,000 dancers (and offered 44 dances) a night, paid one female instructor 30 shillings a week plus tuppence a dance. (Patrons paid sixpence a dance.) This was considered good money indeed. Of course the dance industry kept musicians in work, and professional “exhibition dancers” earned relatively big fees (e.g. £5 a night) giving demonstrations.

Scottish country dancing, although not popular in the urban dance palaces, never died out. Cascioli says it remained popular for clan gatherings, Highland balls, the countryside, and the Scottish nobility (p.113).

By the mid-1950s social dancing in Edinburgh was at its height–and then both slowly and all at once it was murdered by Bill Haley and the Comets (1955)–which is to say, by rock-and-roll music. At first, we are told in Michael Platt’s wonderful 2009 essay “A Different Drummer,” young people “did the Jitterbug and the Lindy to it.” But then, as he continues:

With the Twist, rock ‘n roll found its own step, if that’s the right word, for there is no stepping in it; you just twist. To Twist you don’t need a partner. You are not doing something with another human being. You are either oblivious of others, or displaying yourself to all others. There is nothing to learn, as there was in all dancing before. Never before in civilized society had the feet been fixed. (Take this test: look at a film of people Twisting and turn off the music: what could be more frantic, graceless and, in a way, solitary?

Structured partnered dancing ended, and dancers began to face live bands, when there was one, not each other, and almost nobody took lessons. Fortunately, Scottish country dancing continued as an integral part of Scottish national culture. It continued to be taught in Scottish schools and still is today. But otherwise, only the old folks–like my grandparents–kept up ballroom dances. Eventually the dance palaces became rock clubs or just closed and/or burnt down.

Conclusion

The love of structured partner dances, which remained popular on the Continent and at the English Court, eventually overcame the Calvinist anti-dancing sentiment of Scotland. The pastime of the gentry in the 18th century, it became an essential skill of the Scottish middle classes in the 19th, and the obsession of the working classes in the 20th. Dance parties, called assemblies, began in earnest in 1710, and became increasingly popular until the 1950s. They were soon replaced by undisciplined flailing about in discos, except where there were proper ceilidhs or Scottish country dancing balls. There we still had and have structure and codes of manners of deportment which “introduce politeness among us by a cheerful entertainment which is highly for the advantage of both body and mind.” It is in that spirit that I hope Mrs McLean’s Waltzing Club will continue to flourish.

The original draft of this lecture was delivered by Dorothy McLean in Edinburgh on October 25, 2025.

Thank you to all those who made the Michaelmas Dance 2025 such a success! A very Happy Feast Day to you all. Coorie in!